Analog VS Digital Displays

The often forgotten positive aspects of the round dial Six-Pack

CHAPTER 14

ANALOG VS DIGITAL

LEARNING TO FLY WITH DIGITAL GLASS FLIGHT DISPLAYS

The most obvious problem encountered when conducting primary training in aircraft equipped with a glass panel display resembling a small television screen, is getting the student to not look at it. We work hard to help our students look outside the airplane for attitude awareness, traffic awareness, and to measure control inputs. This is difficult with a conventional aviation six-pack of round dial instruments but becomes exponentially more so with a digital screen a few feet in front of the pilot. These displays are gorgeous, often including niceties like synthetic vision, traffic, and weather information. They are made to be visually stunning and invite the pilot to fly by inside reference while checking outside from time to time, instead of the reverse. This leads to a trained pilot who is less skilled in basic aircraft control by outside visual reference. But there is another reason that these displays are less optimal for primary flight training.

Traditional analog, round dial flight instruments are representative in nature. The hands of a clock don’t really tell what the time is, they represent a certain time which our brain then translates to understand as a point on a 24-hour continuum.

Old Joke Alert! – An air traffic controller says, “Aircraft N12345 you have traffic at 10 O’clock at your altitude, 2 miles, moving left to right.” Pilot replies: “Uh, OK, we don’t know where that is, we have digital watches.”

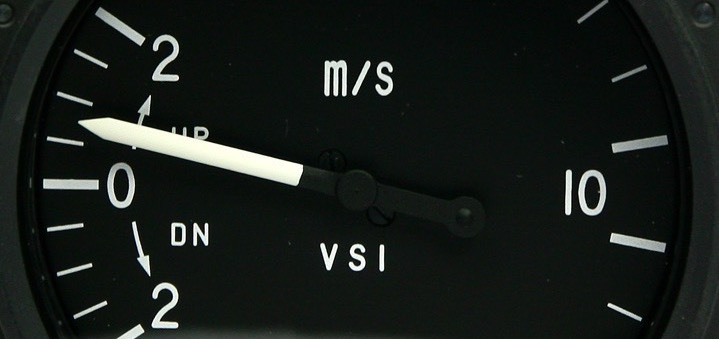

Like a clock face, analog flight instruments are representations of various values. An altimeter with the little hand between the 6 and 7 and the big hand on the 5, means 6500 ft. The skinny hand ending in a white triangle should be a bit more than halfway between 0 and 1, clarifying further that we are at 6,500 not 16,500. This image is therefore incorrect as far as the third hand is concerned.

When we glance at the altimeter, we don’t have to look at the six and the five to verify altitude maintenance. We can see instantly if the big hand has moved away from its previous position. As with the VSI in the inverted V scan, we can see without looking directly at the instrument. Analog versus digital. We process this information by taking a visual/mental picture of the instrument and knowing what it means without having to overtly think about the numbers involved. This mental snapshot process is accomplished with the same side of the brain that does the visual/spatial processing used in basic aircraft control. After only a few hours of practice, absorbing data from analog instruments is easy and very fast, using very little mental bandwidth.

THE TREND

Another positive feature of analog gauges is their easily detected trend information. The rate of movement of the hands tells us how fast things are changing. With more experience, a pilot can detect and use the rate of change within the changing indication, i.e., the acceleration or deceleration of change in needle position. These trend assessments are largely accomplished without active thinking.

Digital Instrumentation

The digital altitude display shown on most glass panel systems is different. Although the position of the black pointer (the background to the digital altitude readout along the vertical altitude “tape” on the right of the display) is analog, the mind is most often attracted to the digits. If 2830 feet is displayed for example, the opposite side of the brain is utilized to read and process this information. Then the pilot mentally translates this number into information which is useful to fly the airplane. Obviously, this task is within our capabilities, and it is done every day, but it takes extra bandwidth to accomplish, and when multiplied times four (altitude, airspeed, vertical speed, and heading) the mental effort adds up. We hear mention of information overload when using glass panel displays in training. It’s not that the display is showing much more than is available from a conventional round dial panel, but that so much of this information is presented digitally and therefore requires mental processing prior to becoming useful data for aircraft control. Trend information, which is processed without conscious effort on analog instruments, is missing from a pure digital display of data. Avionics manufacturers have incorporated separate trend indicators to compensate.

IN A PARFECT WORLD

In a perfect training world, an argument could be made to begin training in an aircraft equipped with conventional round flight instruments, then transitioning to glass displays. However, there is a widespread notion that pilots should train on the most advanced equipment available. Any suggestion that favors older technology is quickly interpreted as nostalgia for “old school” practices, and out of date thinking. Nevertheless, let us not underestimate the challenges that glass displays pose when used in primary flight training. These can be minimized if the flight instructor recognizes the potential pitfalls and takes measures to ensure her students use outside references as primary, and inside information as secondary. The glass panel displays should be dimmed from time to time to allow the student to control the airplane with only the aid of standby instruments. If control skill is reduced when flying without the Primary Display, perhaps additional practice without it is warranted.

Aways practice new flight control concepts and techniques under the supervision of a qualified flight instructor. Without Safety, we have nothing!

©Copyright Charles McDougal 2024

All Rights Reserved